Table of Contents

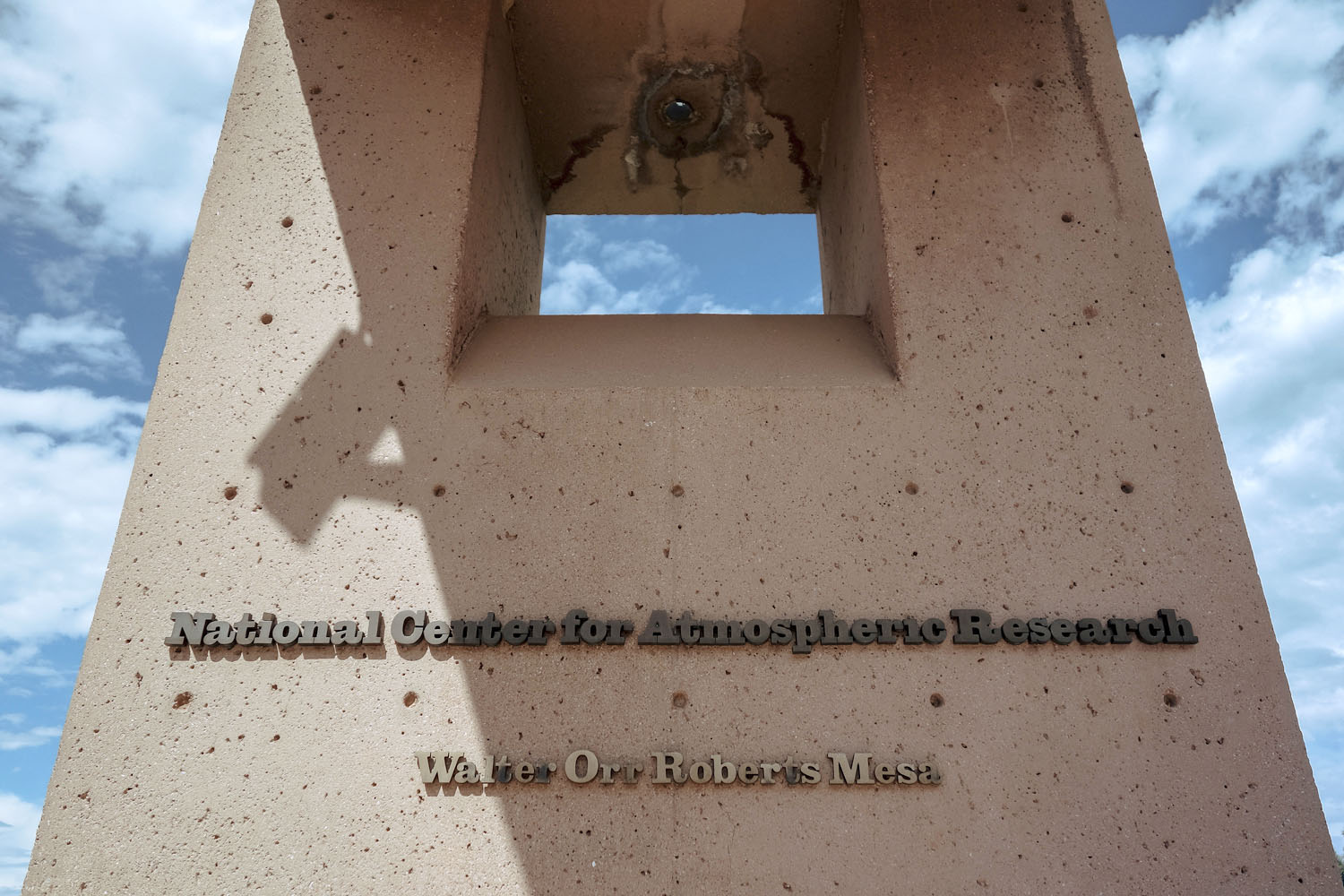

ToggleIt wasn’t until the passing of I.M. Pei that I discovered the entirety of his work in Colorado. Though familiar with the 16th Street Mall, a mile-long pedestrian promenade that’s seedy in parts and attracts mainly tourists, it’s not a place I frequent. After Pei’s death in May 2019, a number of articles began circulating to showcase his best works. This one from the New York Times that highlights one of his commercial architectural creations piqued my interest, with the National Center for Atmospheric Research (also known as the Mesa Lab) in Boulder listed first.

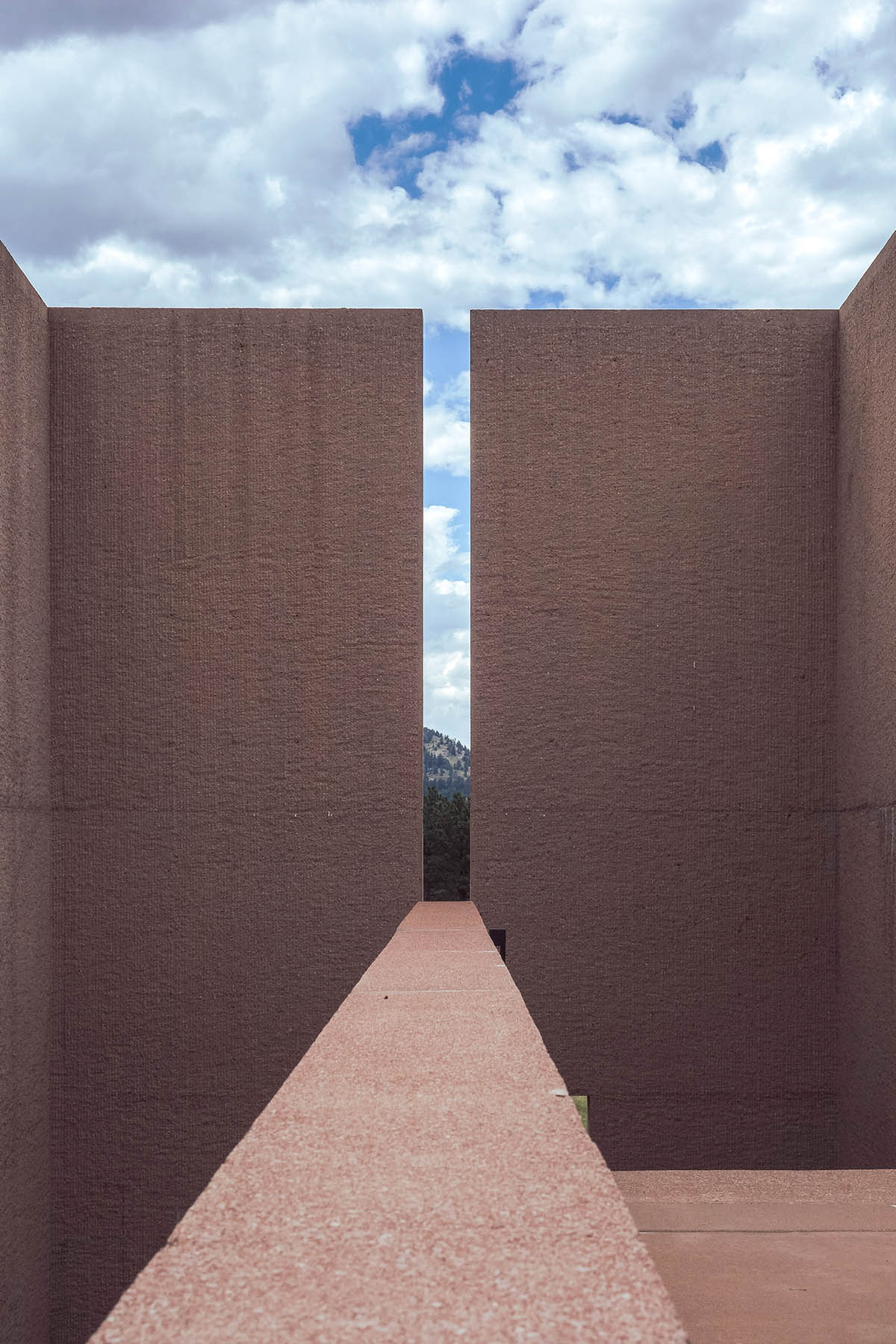

The building complex, comprised of pinkish concrete and stone, is situated on top of a 600-foot mesa with the Flatirons as the backdrop and the Rocky Mountains beyond. Driving up the winding road, the building is so purposefully nestled into the landscape that it doesn’t reveal itself until one is about a mile away. Even then, it’s a glimpse of pink shielded by a wall of vegetation.

Timelessly Modern, Rooted in History

This integration into the landscape is one of the most engaging aspects of the complex, best understood as you meander through the site and the exterior spaces of the building.

But these elements, the natural and the built, are not separate. In fact, the entire complex feels so unified with the landscape that stepping off the paved path onto one of the surrounding trails is barely noticeable. The transition is seamless. Inspired by the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde, the building relates to the landscape without mimicking it. The design reflects an inherent understanding that the architecture must live up to the greatness of the site without becoming its competition. That said, I wouldn’t consider the Mesa Lab delicate or less than. It touches the earth heavily with the use of cast-in-place concrete and stone throughout. Vegetation is wild and native grasses soften where the building meets the earth. Whether this is a strategy to subdue the building mass or the consequence of infrequent landscaping, the result is the same: architecture that surrenders to the site.

“The shapes have been cribbed time and time again. But the spirit of the NCAR building is in context, in the site.” I.M. Pei

A building that stands the test of time, NCAR was completed in 1966 and, in 1997, received the AIA Colorado 25-Year Award.

The Beauty of Restraint

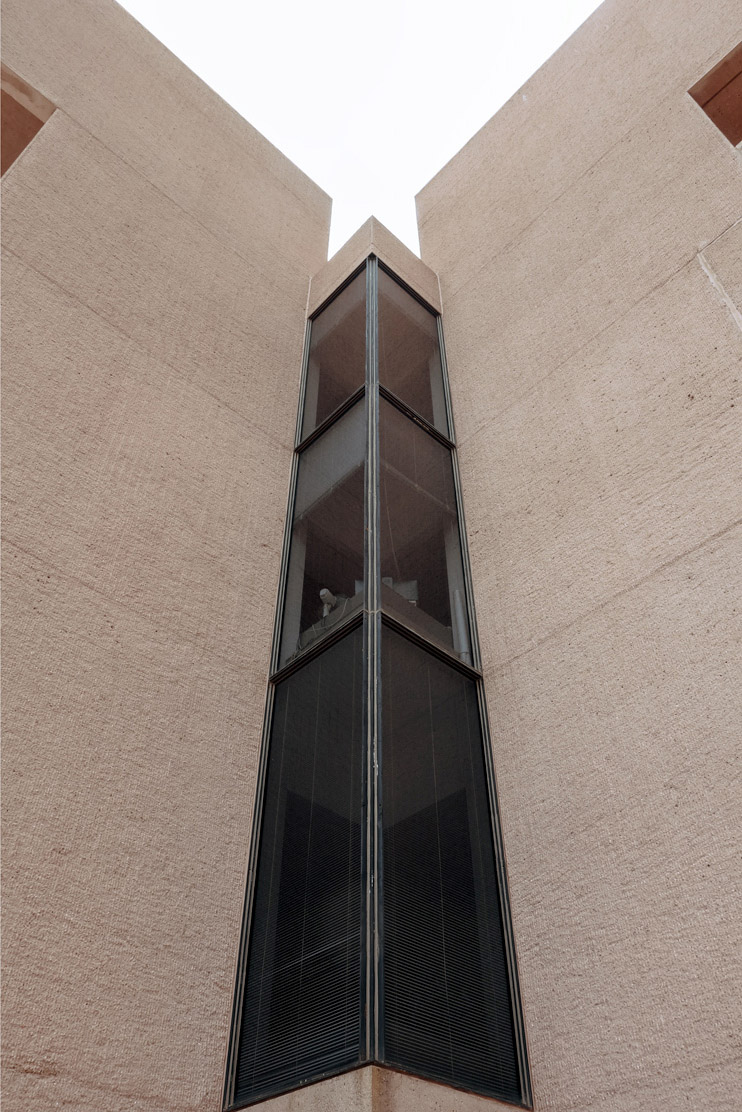

A variety of factors might contribute to the timelessness it boasts. The building still functions as intended. Its form draws from sacred geometry found in ancient architecture. Both are evident and undeniable. But perhaps it’s the materiality, the self-assured use of only three materials throughout the project, that contributes most. It’s a simple, refined palette homogeneous in color, and it feels refreshing.

Take a walk around Denver: you’ll see new construction every few blocks, often displaying four, five, or even six different materials. It begs the question: what is the architect trying to hide? The simplified material selections at the Mesa Lab show confidence in the approach. Certainty in the building mass and form that says, “This is who I am.” Take it or leave it. The Mesa Lab uses what works not only for the massing but also for the context: materials are indigenous to Colorado, with stone quarried from nearby Lyons.

Sacred Geometries

Though Pei keeps the materiality simple, he’s doing the most with the building form.

The use of symmetry throughout creates balance, interest, and dimension. I spent hours at the Mesa Lab, not because I planned to, but because there was something new to experience in each space. Low, rectangular thresholds define the limits of the courtyard on two sides and encourage movement through and into the next exterior room. Sharp architectural lines distinguish between building and nature, creating the axis necessary for symmetry. At times, the architecture reflects the context quite literally, and this feeling of the balance does not go unnoticed. In fact, it heightens the sense that a necessary connection exists between building and landscape. Furthermore, the geometric voids in the massing (square, rectangular, linear, and circular) succeed in framing the surrounding views.

Though I spent most of my time in the exterior spaces of the building itself, I left feeling as though I had enjoyed an afternoon immersed in nature. I left feeling refreshed and excited. The Mesa Lab is as much about architecture as it is about the landscape in which it sits.

“I come back to the city . . . it is rather rigidly geometric. You never can separate a building from the place where it’s standing.”

Olivia Theriot, Architect

Olivia Theriot

A registered Architect, Olivia's professional experience includes luxury residential, multi-family, and mixed-use projects with a focus on contextual sensitivity. Her thesis on how the built environment affects human health and wellbeing shaped her professional and personal life. Raised in Massachusetts, Olivia attended university in Louisiana and currently resides in Denver as an active member of the community and Downtown Denver Partnership.